The Land, The People, The Wars

The Land, The People, The Wars

The Land, The People, The Wars

The significance of this historic cemetery lies in the many chapters of American history reflected across its grounds—war, displacement, economic hardship, and the transfer of land across cultures and generations. As a burial site, it holds the remains of individuals whose lives and experiences shaped the region’s past. Although only a fe

The significance of this historic cemetery lies in the many chapters of American history reflected across its grounds—war, displacement, economic hardship, and the transfer of land across cultures and generations. As a burial site, it holds the remains of individuals whose lives and experiences shaped the region’s past. Although only a few have been identified through research, their presence marks the earliest known use of the property.

For at least ten thousand years, this land was home to the Choctaw Nation, whose territory once encompassed central and southern Mississippi, western Alabama—including present‑day Sumter and Choctaw Counties—and parts of eastern Louisiana.

Pushmataha served from 1799 until his death in 1824, the renowned leader was one of the principal chiefs of the Choctaw people.

The Choctaw and Creek Nations were not perpetual enemies; they traded, intermarried, formed alliances against common threats, and shared cultural practices. Conflicts arose only at times of territorial overlap, raiding, competition for trade, internal political divisions, and—critically—European interference. These outside pressures contributed to internal tensions within the Choctaw Nation, drawing some individuals toward alliances with Creek nation. Pushmataha and most Choctaw leaders, however, favored diplomatic relations and were more open to certain European practices. After the colonization, the Choctaw aligned more with France. The Creek aligned more with the British.

Among the Creek, resistance to European influence helped fuel the rise of Tecumseh’s movement, which encouraged Native nations to unite against U.S. expansion. This unrest contributed to the “Creek War of 1813”, which included the attack on Fort Mims. In response, U.S. forces under Andrew Jackson—supported by Pushmataha and Choctaw warriors—defeated the Red Stick Creek nation within ten months. The Creek Nation ceded 23 million acres in 1814 to the U.S. government.

Pushmataha died in Washington, D.C., in 1824 while advocating for the land and rights promised to the Choctaw Nation. Only a few years later, in 1829, Congress extended state laws over Choctaw territory, effectively abolishing their government. Under mounting pressure, the Choctaw were compelled to cede more than 11 million acres in the 1830 through the “Dancing Rabbit Creek Treaty” to the U. S. government, which included Sumter and Choctaw County Alabama. That same year, Congress passed the “Indian Removal Act”, which forced many Native nations to relocate to Indian Territory in present‑day Oklahoma. The resulting removals—including the Choctaw’s—became known collectively as the “Trail of Tears”, marked by profound suffering, illness, starvation, and loss of life.

Despite these hardships, some Choctaw people remained in the region, forming families and communities—including with enslaved individuals. One such woman was Chammi, a full‑blooded Choctaw whose grandfather had been a prominent war chief. Chammi and her Native American family would make Harris Place Morning Star North Cemetery their final resting place.

Where History Converge

The Land, The People, The Wars

The Land, The People, The Wars

Harris Place Morning Star North Cemetery stands as a testament to the deeply interconnected histories of Native Americans, enslaved Africans, early settlers, and their descendants. From approximately 1650 to 1860, enslaved Africans were forcibly transported to the United States through major ports such as Virginia, South Carolina, and New

Harris Place Morning Star North Cemetery stands as a testament to the deeply interconnected histories of Native Americans, enslaved Africans, early settlers, and their descendants. From approximately 1650 to 1860, enslaved Africans were forcibly transported to the United States through major ports such as Virginia, South Carolina, and New Orleans. Upon arrival, enslavers frequently recorded the date and location of purchase as an enslaved person’s birthdate and birthplace. As a result, the names, ages, and origins assigned to enslaved individuals were often inaccurate or incomplete, leaving significant gaps in the historical record.

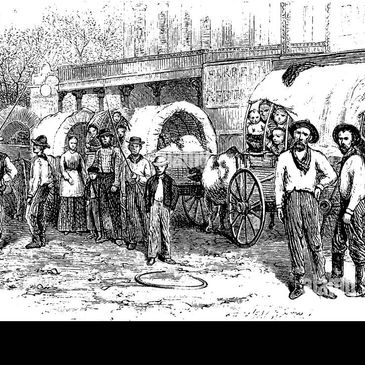

Multiple historical sources confirm that white settlers began entering Creek territory in Alabama after the American Revolutionary War and well before the end of the Creek War in 1813. These settlers crossed into Creek homelands without permission, occupied land that had not been ceded, and contributed to the growing pressure known as “Alabama Fever.”

Many acquired large tracts of land at low cost and brought enslaved people to cultivate it. The enslaved would be chained and brought to the southern states to work the cotton fields and land for the enslaver. Mose and Betsy, along with his brothers arrived in this country around 1810 through the port of Virginia. They were later brought from Virigina to Alabama as enslaved individuals to work the fields for the enslaver. Their family would eventually grow to the hundreds and they were enslaved as well.

Among some of these settlers was Samuel Wallace, an enslaver, a cotton planter, and a soldier under Andrew Jackson at the Battle of Horseshoe Bend in 1814. Originally from Virginia, he moved to Dallas County, Alabama, in 1832 with a land grant and 39 enslaved people; by 1850, he enslaved 95 individuals. Another settler, R. A. Clay, an enslaver, moved first to Autauga County and later to Cuba, Alabama, bringing more than 100 enslaved people with him. Clay played a central role in establishing the town of Cuba and the Rail Station, both built through the labor of enslaved people.

Green Grant, a settler, enslaver, Confederate War veteran, and Sumter County Commissioner, migrated from Greenville, South Carolina. He held the first recorded deed to the cemetery property. Richard Harris, also a settler and enslaver, was born in Abbeville, South Carolina. He moved to Sumter County with his wife, Elizabeth—sister of Green Grant—and their daughter, Laura. Harris established what became known as the Harris Cemetery.

Thomas Devane Bourdeaux, was part of the wave of earliest white settlers who migrated from the eastern seaboard into Alabama and Mississippi. He was born in New Hanover County North Carolina, a region with deep French costal Carolina roots. Thomas relocated to Sumter County where he married Laura Harris, he was a physician and they both were enslavers. Thomas and Laura later moved to Lauderdale County Mississippi with their children just across the state line from Sumter County. This cross-border movement is extremely common as families often owned land or conduct business in both counties.

They had a daughter, Laura, born in 1839 in Sumter County, and she would become the first recorded burial in the Harris Cemetery in 1840. Thomas Bourdeaux served in the confederate army in the 13th Regiment of Mississippi Infantry from 1861-1865.

In 1837, Green Grant purchased 40 acres from the U.S. government and later transferred the land to his brother‑in‑law, Richard Harris. After the Civil War ended in 1865, many enslavers faced severe economic disruption due to the loss of forced labor and began sharecropping with former enslavers. Beginning in the 1880s, the Bourdeaux family began selling portions of their land to formerly enslaved individuals. The Wallace family pooled their resources to purchase significant acreage, including the cemetery site. In the deed of transfer from Bourdeaux to the Wallace family, there was a 5-acre deed restriction for the Harris Cemetery to protect all the previous families who were buried there.

Before the 1880s, enslaved and newly freed people were typically buried on the land of their enslavers, as they did not own property. These burial grounds were often unmarked and located in wooded areas, commonly referred to as slave cemeteries.

Today, Harris Place Morning Star North Cemetery serves as the final resting place for members of the Harris, Bourdeaux, Grant, Enslavers and their families; U.S. and Confederate soldiers; Native Americans; early settlers; enslaved individuals , former enslaved; and generations of their descendants.

A Journey to Freedom and Land

The Land, The People, The Wars

A Journey to Freedom and Land

After the Civil War ended in 1865, formerly enslaved people were legally recognized as free. During this period, Mose, Betsy, and their family were required to choose a surname. After trying several options, they selected the name Wallace. Mose and Betsy were the parents of eight children: Mose Jr., Wash, George, Edward, Martha, Caroline,

After the Civil War ended in 1865, formerly enslaved people were legally recognized as free. During this period, Mose, Betsy, and their family were required to choose a surname. After trying several options, they selected the name Wallace. Mose and Betsy were the parents of eight children: Mose Jr., Wash, George, Edward, Martha, Caroline, Henry Clay, and Thornton.

Mose, Betsy, Mose’s brother Henry, and their families remained in the area and worked as sharecroppers for their former enslavers, while other relatives moved north in search of better opportunities. The Wallace family took on additional work and saved diligently with the goal of purchasing their own land.

Beginning in 1880, formerly enslaved families in the community began acquiring land from the Bourdeaux family and other former enslavers. In 1887, the Wallace family purchased approximately 500 acres from the Bourdeaux family, including the five-acre Harris Cemetery. Their deed included a restriction requiring that the cemetery be preserved and protected in perpetuity for the families already buried there. After the purchase, the Wallace family divided the land among themselves.

Henry Clay Wallace eventually came to own more than 225 acres, including the Harris Cemetery. In 1882, he married Lou Gibbs, daughter of Wesley Gibbs. Lou’s mother passed away when she was young, and her father later remarried. Henry and Lou raised a large family: Mariah, John, Henry Jr., Chaney, Matthew, Joseph, Annie Clay, Mary, Emma, and Robert.

Henry Clay played a central role in shaping what became the Morning Star Community. Working alongside Henry James Walker and Charles Gibbs, he helped transition the area from its earlier name, “Old Dove Town,” and contributed to the establishment of the McGowen School. The local church was renamed Morning Star Baptist Church, where all three men served as deacons. They also supported renaming Harris Cemetery to Morning Star Cemetery. Many residents of the community were connected through blood or marriage.

In 1918, Henry and Lou’s sons—Robert, Matthew, and Joseph—were drafted into World War I. Matthew was killed in combat. That same year, Lou Wallace died during a devastating flu outbreak, followed shortly by their children Mary and Joseph. Lou’s grandmother, Chammi, had already passed away. Despite these losses, Henry Clay continued farming with the support of his children and grandchildren until his death in 1937 from injuries sustained in a fall from his truck.

A defining part of Henry Clay’s legacy was his commitment to protecting the cemetery and safeguarding the graves of those already laid to rest. Today, the Harris Place Morning Star North Cemetery serves as the final resting place for many members of the community; including Henry Clay Wallace, Lou Wallace, Mose and Betsy Wallace, Mary Wallace, Joseph Wallace, Lou’s mother, their families and numerous descendants. Others buried there include formerly enslaved families, enslaver's families, Chammi - a full blooded choctaw indian, Richard and Elizabeth Harris, Green Grant, Thomas and Laura Harris Bourdeaux, Laura Bourdeaux, Catherine Bourdeaux, World War I & II veterans, U.S. & Confederate soldiers, early settlers, Native Americans, and many more.

Henry Clay bequeathed his property—including the cemetery—to his children and grandchildren, with the instruction that it remain within the Morning Star Community, never be sold, and stay in the family for generations. Ras Miller, who eventually inherited 40 acres including the cemetery, believed he was preserving his grandfather’s legacy when he signed legal documents. Unaware of their true implications, he unintentionally transferred ownership of part of the land. Although he was able to correct some of the error, he passed away before resolving the remaining portion, which was still in court. It is believed he was experiencing dementia at the time. Chammi, who was a full blooded choctaw indian, was the grand mother of Ras Miller's wife Ada Gibbs.

Over time, the cemetery became overgrown due to lack of maintenance. It was further damaged during an unauthorized timber harvest, resulting in the loss of headstones, markers, trees, and other features that once helped families locate gravesites. As a result, many burial locations and identities were lost.

Today, efforts to restore and document the cemetery rely on family memories, personal records, U.S. Census data, historical documents, Ancestry research, and geological and genealogical resources. Significant progress has been made with support from the Alabama Historical Commission, the University of Alabama, University of West Alabama, in-kind services, and small donations.

If you have additional information about this cemetery—formerly known as Harris Cemetery, Morning Star Cemetery, or Wallace Cemetery or individuals who were buried there between 1840-1960 and related to the Wallace, Walker, Gibbs, Nixon, Miller, Ruffin, Brunson, Wilson, Eades, Sturdivant, Hull, Knighton, Nickerson, McGrew, Casteele, Bell, Blakely, Hatten, Poe, Gaston, Hare, Larde, McGowen, Hopson, Nelson, Straight, Collins, Pickens, Wiggins, Lake, Delaine, McAboy, Young, Spears, Watson, Grant, Harris, and Bourdeaux. Please contact us at

before and after pictures of the cemetery

Help Our Cause

Your support and contributions will enable us to meet our goals and improve conditions. Your generous donation will fund our mission. We are accepting donations to help restore the cemetery and install a headstone for each gravesite that was loss or destroyed. All donations are tax deductible and recognized by the Internal Revenue Service as a tax exempt organization.

help is needed

Please sign up to volunteer, donate, provide historical information or serve on a research committee. Please join us.

Contact Us

morningstarcemetery2@gmail.com

Please make all donations to Harris Place-Morning Star North Cemetery. Send all donations to 4044 Dove 2 Cuba, Alabama 36907. All donated funds will be used towards the restoring of the cemetery and funds in excess of the expenses, shall be placed in an operating fund for future operational expenses of the cemetery.

Harris Place-Morning Star North Cemetery

4590 Dove 2 Cuba, Alabama 36907, United States

Hours

Monday - Friday : Open

Saturday: Open

Sunday: Open

Welcome

There's much to see here. So, take your time, look around, and learn all there is to know about us. We hope you enjoy our site and take a moment to drop us a line.